Under the Shadows of Gender Violence: An Exploration of Sexual Consent through Spanish University Women’s Experiences

[Bajo la sombra de la violencia de género: una exploración del consentimiento sexual a través de experiencias de mujeres estudiantes universitarias españolas]

Edgardo Gomez-Pulido, Marta Garrido-Macías, Cynthia Miss-Ascencio, and Francisca Expósito

University of Granada, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2024a10

Received 2 May 2024, Accepted 3 July 2024

Abstract

Introduction: This article addresses the complex dynamics of sexual consent among female Spanish university student. The research is based on two independent studies, each employing a distinct methodology: study 1 (n = 308) employs a quantitative approach to analyze the relationship between the endorsement of heterosexual scripts, individual variables (sexual satisfaction, sexual assertiveness, and sexual communication styles), and intimate partner sexual violence (IPSV) and the reasons for consenting to unwanted sex; study 2 utilized qualitative methods to explore personal narratives and deepen the understanding of consent as experienced and articulated by 8 women. Objectives: Study1 aimed at quantitatively assessing how the endorsement of heterosexual scripts, individual variables, and previous IPSV experiences impact the reasons for consenting to unwanted sex. Study 2 sought to compliment Study 1’s findings and qualitatively investigate the personal and societal narratives that shape the understanding and communication of sexual consent. Results: In Study 1, the findings reveal that endorsements of traditional sexual scripts and histories of IPSV are associated with a higher likelihood of consenting to unwanted sex, while greater sexual satisfaction and assertiveness correlate with reduced consent to unwanted sex. Study 2 provides a thematic exploration of sexual consent, identifying key themes in how consent is negotiated, perceived, and misunderstood within interpersonal and cultural contexts. Conclusions: The combined results of these studies illustrate the nuanced interplay between individual agency, cultural expectations, and past experiences in shaping sexual consent. Underscoring the importance of challenging traditional sexual scripts and enhancing assertiveness, this research contributes to ongoing efforts to foster a consent culture that respects individual boundaries and desires in sexual relationships.

Resumen

Introducción: El artículo aborda la compleja dinámica del consentimiento sexual en estudiantes universitarias españolas. La investigación se basa en dos estudios independientes, cada uno empleando una metodología distinta: el estudio 1 (n = 308) utiliza un enfoque cuantitativo para analizar la relación entre la adhesión a los guiones heterosexuales, variables individuales (satisfacción sexual, asertividad sexual y estilos de comunicación sexual) y la violencia sexual en la pareja (VSP) y las razones para consentir sexo no deseado; el estudio 2 utiliza métodos cualitativos para explorar narrativas personales y profundizar en la comprensión del consentimiento tal como lo experimentan y articulan 8 mujeres. Objetivos: El estudio 1 se propuso evaluar cuantitativamente cómo afectan los motivos para consentir al sexo no deseado la adhesión a los guiones heterosexuales, las variables individuales y las experiencias previas de VSP. El estudio 2 pretende complementar los hallazgos del estudio 1 e investigar cualitativamente las narrativas personales y sociales que configuran la comprensión y comunicación del consentimiento sexual. Resultados: En el estudio 1, los resultados indican que la adhesión a los guiones sexuales tradicionales y los antecedentes de VSP están asociados con una mayor probabilidad de consentir sexo no deseado, mientras que una mayor satisfacción sexual y asertividad correlacionan con un menor consentimiento al sexo no deseado. El estudio 2 proporciona una exploración temática del consentimiento sexual, identificando temas clave en cómo se negocia, percibe y malinterpreta el consentimiento dentro de contextos interpersonales y culturales. Conclusiones: Los resultados combinados de estos estudios ilustran la interacción matizada entre la acción individual, las expectativas culturales y las experiencias pasadas en la configuración del consentimiento sexual. Subrayando la importancia de desafiar los guiones sexuales tradicionales y mejorar la asertividad, la investigación contribuye al esfuerzo continuado por fomentar una cultura de consentimiento que respete los límites y deseos individuales en las relaciones sexuales.

Keywords

Sexual consent, Gender violence, Unwanted sex, RevictimizationPalabras clave

Consentimiento sexual, Violencia de gĂ©nero, Sexo no consentido, RevictimizaciĂłnCite this article as: Gomez-Pulido, E., Garrido-Macías, M., Miss-Ascencio, C., & Expósito, F. (2024). Under the Shadows of Gender Violence: An Exploration of Sexual Consent through Spanish University Women’s Experiences. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 16(2), 111 - 123. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2024a10

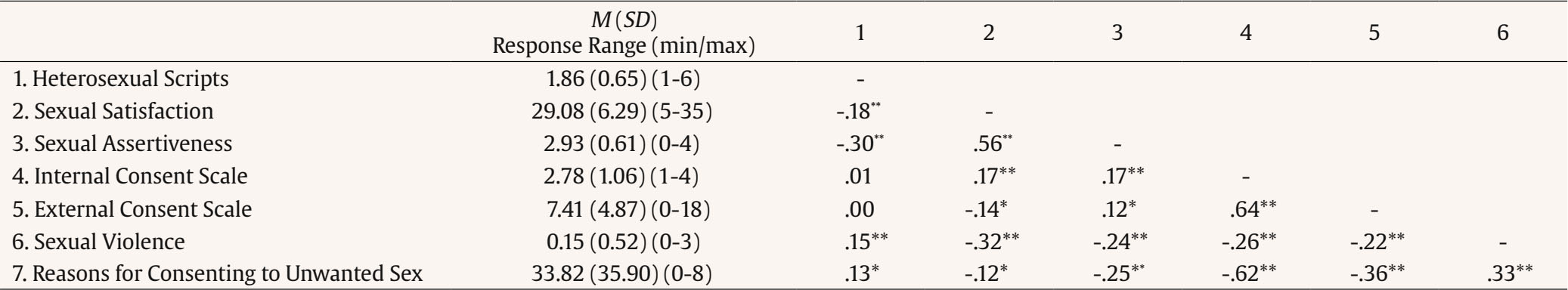

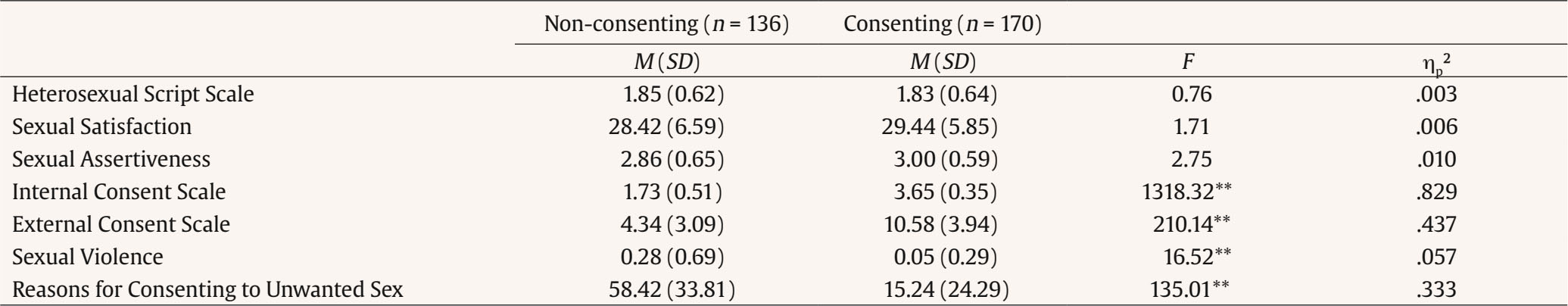

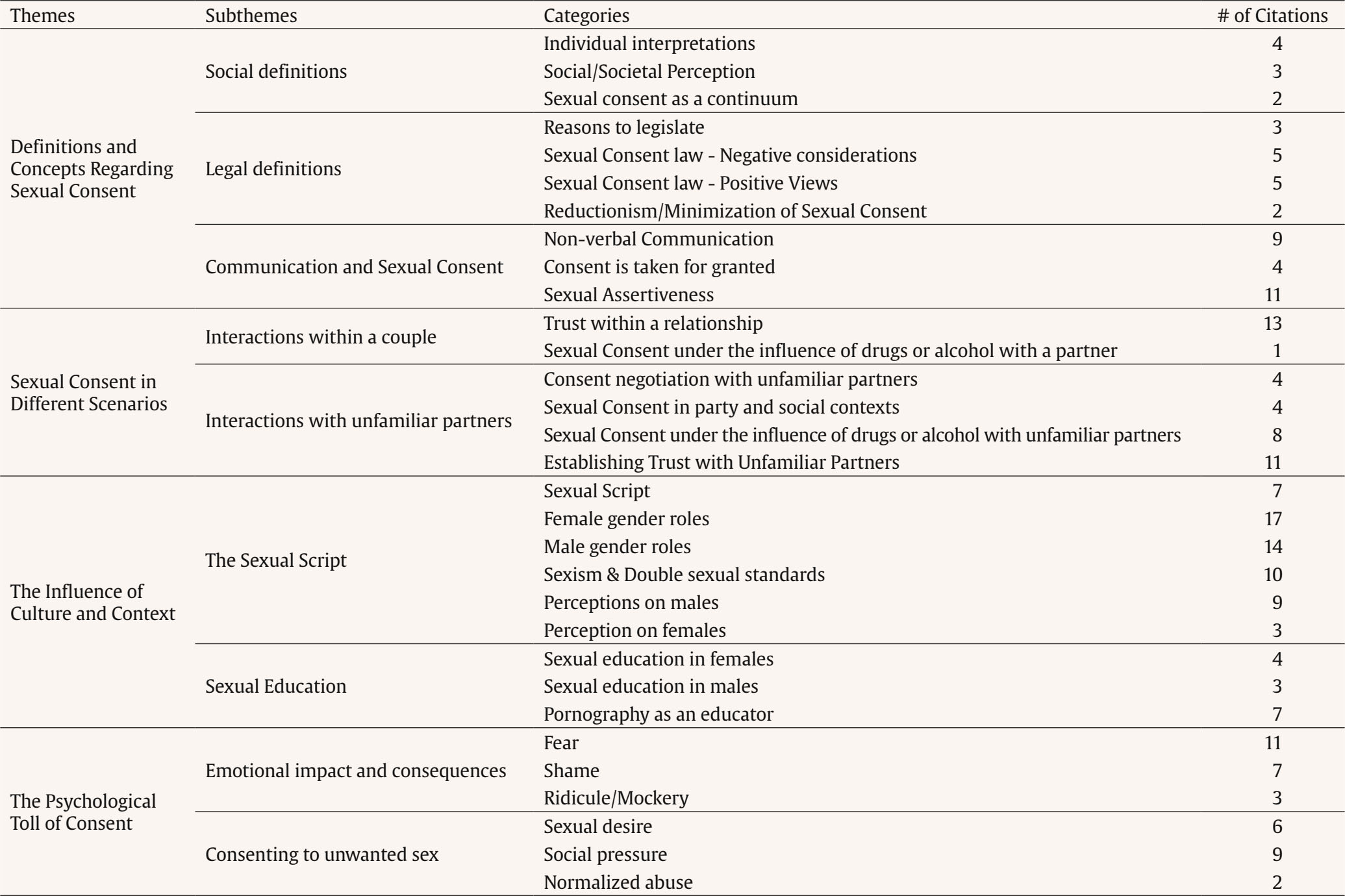

Correspondence: marta.garrido@uma.es (M. Garrido-Macías); david.martinez@universidadeuropea.es (D. Martínez-Rubio).Sexual violence has been defined as sexual activity without consent (Beres, 2014), placing sexual consent as a major element for establishing healthy and safe sexual interactions. Nonetheless, determining the specific parameters for establishing sexual consent poses a considerable challenge within both the legal and academic domains. In Spain, a legal initiative was undertaken to address the issue of sexual violence and provide legal support to its victims through the drafting of Spanish law of sexual freedom (Ley Orgánica 10/2022, de 6 de septiembre, de garantía integral de la libertad sexual [L.O. 10/2022], 2022). This law emphasizes the relevance of affirmative sexual consent, commonly known as “Yes means yes.” One of its primary goals is to establish a clear understanding of what constitutes consent in sexual encounters. According to this law, consent is deemed present only when it is freely expressed through actions that unequivocally demonstrate a person’s intention, considering the specific circumstances of the situation (L.O. 10/2022, 2022). However, due to the broad nature of this definition, it has garnered equally both advocates and critics. The problem of defining sexual consent is not lightened in academic circles either. In recent literature, the significance of clearly defining and communicating sexual consent has been extensively discussed. Ågmo and Laan (2024) emphasized that sexual interactions require consent at every stage, which is crucial for ensuring mutual satisfaction and preventing unwanted sexual experiences. Still, sexual consent remains an ambiguous term in the research literature (Beres, 2007). This ambiguity has been suggested as a factor that facilitates the continued prevalence of sexual assault despite efforts aimed at informing young people about sexual consent because it complicates the establishment of clear and consistent standards for consensual interactions, leading to misunderstandings and miscommunications (Fenner, 2017). Nontheless, efforts have been made in an attempt to define sexual consent. Hickman and Muehlenhard (1999) conceptualized it as the freely given verbal or non-verbal communication indicating willingness to engage in a sexual activity. Other researchers defined it as one’s voluntary, sober, and conscious willingness to engage in a specific sexual behavior with a particular person within a particular context (Willis & Jozkowski, 2019). These definitions address different features: the internal aspect, which is the voluntary and internal decision to engage in a particular sexual activity (Willis et al., 2019), and the external aspect, which involves what individuals do or say to express consent, whether verbal or non-verbal, explicit or implicit (Willis et al., 2019). Despite verbal communication being the most effective means of establishing consent, research on sexual consent behavior reveals a predominant reliance on nonverbal signals, which are often accorded greater trust and usage compared to explicit verbal expressions of consent (Beres et al., 2004; Fenner, 2017; Jozkowski, Sanders, et al., 2014; Muehlenhard et al., 2016; Willis et al., 2019). However, relying on nonverbal cues can lead to misinterpretations, particularly affecting women, as men tend to interpret situations as more consensual (Jozkowski, Peterson, et al., 2014). Building on all these difficulties surrounding the concept of sexual consent, our main goal is to uncover deeper understandings of sexual consent, contributing to a clearer and more comprehensive framework for addressing sexual violence and promoting healthier and more responsible sexual interactions. In this regard, the negotiations that take place within the framework of these sexual interactions are influenced by a handful of variables that end up determining the way in which they occur. Therefore, in this article, we aim to dissect the intricate dynamics of sexual consent, examining the endorsement of heterosexual scripts, individual variables (sexual satisfaction, sexual assertiveness, and sexual communication styles), and intimate partner sexual violence (IPSV) experiences, contrasting them against the women’s narratives to provide a deeper understanding of the forces that mold interactions surrounding sexual consent. Endorsement of the Heterosexual Script Sexual interactions between men and women are by no means free from social influences. The way sexual interactions navigate to establish (or not) sexual consent will be given by the sexual script. This theory, initially described by Simon and Gagnon (1984), outlines the way men and women are socialized to behave in sexually laden situations. People who endorse the traditional sexual script expect men to always want, seek, and be ready for sex, therefore, reducing inhibitions about their internal sexual desires and feelings of consent to engage in a particular sexual activity (Jozkowski, Sanders, et al., 2014). Asymmetrically, women are typically socialized in opposite patterns: they are expected to behave in sexually explicit manners to attract male attention (Armstrong et al., 2006; Jozkowski, Sanders, et al., 2014) but also to avoid promiscuity (Brown, 2002; Jozkowski, Sanders, et al., 2014; Muehlenhard & McCoy, 1991) which generates internal conflicts (Jozkowski, Sanders, et al., 2014). Additionally, women have been subject to discrimination and oppression in many societies, contributing to the maintenance and reinforcement of hierarchies and gender inequities in gendered contexts (Pratto & Walker, 2004). Moreover, the pressure of society traditional gender roles may adversely impact women’s sexual health, as it can lead to feelings of sexual pressure and acquiescence to unwanted sexual activities (Scappini & Fioravanti, 2022). For example, Kiefer and Sanchez (2007) found that endorsement of traditional sexual roles are linked with increased sexual passivity for women, which predicts poor sexual functioning and satisfaction. Additionally, adherence to traditional gender roles has been shown to have a negative impact on women’s sexual satisfaction and agency, leading to more instances of non-consensual sexual encounters (Sanchez et al., 2012). Understanding the interplay between sexual script expectations and sexual consent can enlighten us on power imbalances and gendered dynamics in sexual relationships. Acknowledging these factors is key to challenging harmful norms and fostering a positive consent culture, where individuals can express their boundaries and desires freely. This insight is crucial for creating interventions that empower individuals, particularly women, to navigate sexual interactions with autonomy and awareness, aiming to strip down coercion strategies and promote equality in all sexual encounters. For the purposes of this article, when we refer to “individual variables,” we are addressing those aspects that are acted upon or felt at a personal level by the individuals involved, rather than beliefs or scripts shared collectively by society. These individual variables include personal feelings, experiences, and behaviors that influence one’s decisions and actions in the context of sexual consent and intimate partner interactions. For instance, every sexual encounter should ideally be consensual and driven by a shared desire. These internal feelings of consent, which refer to the mental act of being willing or wanting to engage in a sexual activity, have a significant role in ensuring a positive and mutually satisfying sexual experience for all involved (Walsh et al., 2019). As explained before, according to research, when it comes to communicating consent, nonverbal communication tends to be more common than verbal communication, and indirect communication tends to be more common than direct communication (Fenner, 2017). Additionally, most young people use a mix of verbal and nonverbal signals to convey their consent, or lack thereof, although there are some slight variations based on gender (Fenner, 2017). Jozkowski, Sanders, et al. (2014) suggest that differences in communication styles from males and females can lead to misunderstandings and miscommunications that increase the risk of non-consensual or coercive sexual encounters. The ways individuals convey sexual consent and the ability to communicate and express it may also be directly related to sexual assertiveness, which is defined as the use of outward conduct to communicate what one wants, including what one desires (or does not) sexually, as well as advocating for safe sex methods (Morokoff et al., 1997). Sexually assertive women may be more prepared to express refusal to undesired sexual interactions as well as give consent to desired sex. Findings by Jones et al. (2024) indicate that women may feel pressured to conform to the desires of their more powerful partners to maintain the relationship or social standing, this way stressing the need for assertiveness to ensure that consent is genuinely free and mutual, rather than constrained by implicit pressures (Jones et al., 2024). Low sexual assertiveness, for example, has been linked to an increased risk of sexual victimization for women (Livingston & Vanzile-Tamsen, 2007; Mac Greene & Navarro, 1998). Higher sexual assertiveness, on the other hand, has been shown to be connected with lower incidence of sexual victimization (Mac Greene & Navarro, 1998; Walker et al., 2011). When it comes to sexual aggression, the ability to link sexual desire with sexual consent by being sexually assertive appears to also be a significant aspect (Darden et al., 2018). Additionally, the way women navigate consent in their relationships, according to the literature, may have a direct effect on their sexual satisfaction. Katz and Tirone (2009) informed that consenting to unwanted sexual activity reported less sexual satisfaction than women who did not. Similarly, Vannier and O’Sullivan (2011) found that women who acquiesced to unwanted sexual activity also described it as less enjoyable than desired sexual experiences. Moreover, women may engage in unwanted sexual activity since society favors compliant or passive behavior in women, and such behaviors are viewed as positive (Morgan et al., 2006). Thus, a better understanding of the relationship between sexual consent and variables such as sexual satisfaction, sexual assertiveness, and sexual communication styles may help prevent the negative consequences related to sexual compliance. It is an objective of this article to explore how the interplay between these factors can enable women to more actively engage in sexual experiences that are consistent with their own desires, effectively communicate their boundaries, and confidently assert their needs and preferences. Intimate Partner Sexual Violence Experiences (IPSV) A large body of research has demonstrated that women who have experienced non-consensual sexual interactions face an increased risk of being revictimized, although the specific mechanisms underlying this risk are not yet fully understood (Culatta et al., 2020; Edwards & Banyard, 2022; Garrido-Macías et al., 2020). Garrido-Macías et al. (2022) found that having experienced previous sexual coercion from an intimate partner and being committed to the relationship may be factors that increase women’s tolerance towards situations involving the risk of sexual victimization. Similarly, revictimized individuals often exhibit greater self-blame and shame (Breitenbecher, 2001). Furthermore, individuals who have been revictimized are also more likely to experience distress and psychiatric disorders, as well as difficulties in interpersonal relationships, coping, self-representations, and affect regulation (Breitenbecher, 2001). Research indicates that sexual victimization is an especially significant issue among university students (Anyadike-Danes et al., 2024; Camp et al., 2018; Muehlenhard et al., 2017), with approximately 20 to 25% reporting an unwanted sexual experience during their time at a U.S. university (Anyadike-Danes et al., 2024; Kilpatrick et al., 2007; Krebs et al., 2007). While extensive studies have been conducted on sexual consent and its related variables, there is a notable lack of research specifically focusing on Spanish female university students. Understanding the unique cultural, social, and educational contexts of this demographic is crucial for developing effective interventions and support systems. This study aims to fill this gap by examining the dynamics of sexual consent, heterosexual script endorsement, individual variables, and intimate partner sexual violence experiences within a sample of Spanish female university students. By addressing this under-researched population, we hope to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of sexual consent and promote healthier, more consensual sexual interactions. Ultimately, developing a comprehensive understanding of sexual consent and its related variables may give women tools to assert their boundaries and desires but also to contribute to the creation of a society that prevents sexual victimization more effectively and prioritizes consent, respect, and the overall sexual health and well-being of all its members. This study attempted to evaluate the extent to which the endorsement of heterosexual scripts, individual variables (sexual satisfaction, sexual assertiveness, perceptions and feelings of consent, and verbal/behavioral cues used in sexual interactions) and IPSV experiences are associated with the endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sex in Spanish female undergraduate students. Specifically, our hypotheses were the following: Hypothesis 1: Women who report a higher endorsement of traditional sexual scripts will also report higher endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sex. Hypothesis 2: Higher scores in sexual satisfaction (2a) and sexual assertiveness (2b) will be negatively related to the endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sex. Hypothesis 3: Higher usage of verbal/behavioral cues to communicate consent (3a) and feelings and perceptions of consent (3b) will be negatively related to higher endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sex. Hypothesis 4: Participants that have experienced intimate partner sexual violence experiences will also have a higher score in the endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sex. Hypothesis 5: Participants that have experienced a sexual activity without giving full consent (vs. participants who have not had ‘no consent’ sexual experiences) will significantly have higher endorsement of traditional sexual scripts (5a), lower scores in sexual satisfaction (5b), sexual assertiveness (5c), and internal and external consent (5d) respectively, experienced higher IPSV rates (5e), and have higher endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sex (5f). Method Participants A total of 540 undergraduate women started this study. Thirty of them were removed for being of a different nationality than Spanish, 183 due to incomplete or blank surveys, and 19 participants because they did not identify as heterosexual or bisexual, or because they had never engaged in sexual relationships with men. Thus, our analytic sample consisted of 308 females. Participants were, on average, 21.96 years old (SD = 3.60), ranging from 18 to 44. Participants tended to be exclusively attracted to males (n = 190, 61.70%), while the remaining participants stated to be attracted to both men and women (n = 118, 38.3%). Participants were students on a three-year undergraduate program (n = 35, 11.4%), a four-year undergraduate program (n = 233, 75.6%), or a post-graduate program (n = 40, 13%). The sample size was calculated by means of a G*Power version 3.1.9.7 program (Copyright © Franz Faul, Universitat Kiel, Germany). For correlation analysis, the necessary sample size was 282 to account for .05 of significance, .80 of testing power, and an effect size of r = .03 (medium effect size in Social Psychology studies; Richard et al., 2003). For the MANOVA test, the necessary sample size was 248 to account for .05 of significance, .80 of testing power, and an effect size of f = .06 (medium effect size in Social Psychology studies; Richard et al., 2003). Design and Procedure Participants were recruited by using a daily campus-wide e-newsletter at the University of Granada to complete a cross-sectional design where interested students could participate by clicking the recruitment link provided. The survey included a set of sociodemographic items and was administered using Qualtrics survey software. To be eligible, participants had to be female, Spanish, at least 18 years old, be enrolled in a University of Granada program, must identify as heterosexual or bisexual and have had at least one sexual relationship with a man. All participants were informed about the study’s purpose, its voluntary nature, and the anonymity of their responses. Once participants gave their consent by the Declaration of Helsinki, they were instructed to answer the measures of interest, which took them approximately 30 minutes. Although no monetary compensation was provided for participation, interested participants that completed the survey would be eligible to participate in a €50 raffle once the study finished. This study had the approval of the Ethics Committee of the University of Granada for studies involving human participants. Measures Heterosexual Script Scale (HSS). The HSS (Spanish version by Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2023) assesses the level of endorsement of the complimentary but opposing roles that women and men are expected to play in their romantic and the sexual interactions. The scale is composed of 22 items (e.g., “There is nothing wrong with men being primarily interested in a woman’s body,” where participants are asked to rate their degree of agreement with each statement on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). The overall score is calculated by averaging the item responses, with higher scores indicating a stronger endorsement of heterosexual scripts. The original HSS (Seabrook et al., 2016) showed an internal consistency value of .88. In the present study, HSS Cronbach’s alpha was .87. Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction (GMSEX; Sánchez-Fuentes & Sierra, 2015). This instrument is used to assess sexual satisfaction in the context of relationships. The GMSEX is composed of five seven-point bipolar scales (very bad – very good; very unpleasant –very pleasant; very negative –very positive; very unsatisfying – very satisfying; worthless –very valuable). The minimum score in this scale is 5 and the maximum score is 35. The responses of participants were summed, with higher scores reflecting greater sexual satisfaction. Hurlbert Index of Sexual Assertiveness (HISA). This instrument (Spanish version by Sierra et al., 2008) assesses the degree of assertiveness (initiation and rejection of sexual activity) in the context of relationships. It is comprised of 25 items (e.g., “I find myself having sex when I do not really want it”) with a Likert type scale ranging from 0 = never to 4 = always). The overall score is calculated by averaging the item responses, with higher scores indicating greater sexual assertiveness. An internal consistency value of .90 was found by Sierra (2008) using this version of the instrument. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .89. Internal Consent Scale (ICS; Jozkowski, Sanders, et al., 2014). ICS assesses a range of feelings that the participants may experience and contribute to their decision to consent to a sexual activity. It consists of 25 items that use a four-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1(strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) and factors include Physical response (six items: e.g., “I felt rapid heart beat”), Safety/Comfort (seven items: e.g., “I felt comfortable”), Arousal (three items: e.g., “I felt aroused”), Agreement/Wantedness (five items: e.g., “The sex felt agreed to”), and Readiness (four items: e.g., “I felt sure”). The overall score is calculated by averaging the item responses, with higher scores indicating stronger internal consent. In accordance with the usual standards, a translation and back-translation process was performed (English-Spanish/Spanish-English. Jozkowski, Sanders, et al., (2014) found an internal consistency value of .97 for this instrument. The alpha score for this scale was .98 for this study. The External Consent Scale (ECS). The ECS (Jozkowski, Sanders, et al., 2014) assesses the behavioral and verbal cues used to convey sexual consent. It consists of 18 items using dichotomized response choice (1-Yes and 0-No). The ECS is divided in five individual factors: Nonverbal behaviors (five items: e.g., “I increased physical contact between myself and my partner”), Passive behaviors (four items: e.g., “I did not say no or push my partner away”), Communication/Initiator behaviors (three items: e.g., “I used verbal cues such as communicating my interest in sexual behavior or asking if he/she wanted to have sex with me”), Borderline pressure behaviors (three items: e.g. “I shut or closed the door”), and No response signals (three items: e.g. “I did not say anything”). In accordance with the usual standards, a translation and back-translation process was performed (English-Spanish/Spanish-English. The total score is calculated by summing the items, the minimum score and maximum scores in this scale are 0 and 18, respectively, with higher scores indicating a greater use of external consent behaviors. Sexual Consent Experiences. Participants were asked if they had had any sexual activity in which they did not feel comfortable because they did not have given their full consent. The answer to this question was used to divide the sample into two subgroups. If they answered “yes” (Non-consenting, n = 136), they were asked to respond to the Internal Consent Scale and the External Consent Scale, thinking about that specific sexual interaction. Otherwise, the original ICS and ECS questionnaires were provided without any modifications (Consenting, n = 170). WHO’s Screening for Intimate Partner Violence: Sexual Violence Subscale (World Health Organization, 2003). It is composed by 3 dichotomous items to asses experiences of intimate partner sexual violence (e.g., “Did you ever have sexual intercourse you did not want to because you were afraid of what your partner or any other partner might do?”). The total score is calculated by summing the items, with a minimum score of 1 and a maximum of 3, with higher scores indicating higher intimate partner sexual violence. In accordance with the usual standards, a translation and back-translation process was performed (English-Spanish/Spanish-English). Reasons for Consenting to Unwanted Sex Scale (RCUSS; Humphreys & Kennett, 2010). This instrument was developed to assess the amount of endorsement women give to different reasons for which they consented to engage in sexual activities that they did or did not desire. The scale consists of 18 items (e.g., “As his girlfriend, I am obligated to engage in the unwanted sexual activity,” using a 9-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = not at all characteristic of me to 8 = very characteristic of me. The total score is calculated by summing all the items, with minimum and maximum scores of 0 and 144, respectively. In accordance with the usual standards, a translation and back-translation process was performed (English-Spanish/Spanish-English). Sociodemographic Variables. Participants reported their age (measured in years), sexual orientation, and relationship status. Analyses Collected data was imported into SPSS 28.0, which was the program used to conduct the preparation, descriptive statistics, and bivariate associations. Correlations assessed associations between the endorsement of heterosexual scripts, individual variables, and IPSV experiences related to the endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sex (see Table 1). We also conducted a MANOVA to explore differences between the Consenting and Non-consenting groups (see Table 2) regarding the endorsement of heterosexual scripts (5a), individual variables (sexual satisfaction, 5b; sexual assertiveness, 5c; and internal and external consent, 5d), IPSV experience (5e), and reasons for consenting to unwanted sex (5f). Specifically, sexual consent was used as the independent variable, and heterosexual scripts, sexual satisfaction, sexual assertiveness, internal and external consent, IPSV experience, and reasons for consenting as dependent variables. Sexual orientation and relationship status were included as covariables. All tests were conducted at an α-level of .05. Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations, and Bivariate Correlations between Variables   N = 327. Higher scores indicate greater standing on the variable. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.> Results Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Descriptive statistics for all variables are reported in Table 1. First, regarding the endorsement of heterosexual scripts, the average score across all participants indicated a low level of endorsement of traditional roles expected for women and men in their romantic and the sexual interactions to play. Concerning individual variables, the average score across all participants indicated that most of the sample had high scores of sexual satisfaction (GMSEX). The participants demonstrated a fairly high level of sexual assertiveness (Hurlbert Index of Sexual Assertiveness), with an average response above the midpoint value of the scale (2). This means that, on average, the participants exhibited assertive sexual behavior and attitudes. Internal Consent Scale’s mean score indicated fairly positive feelings associated with participant’s decision to consent to sex across the sample. The External Consent Scale’s mean score was relatively low in the sample, suggesting that participants tended to rely more on passive cues when communicating consent or non-consent, rather than verbal ones, and indicating that there is room for improvement in how women communicate consent in sexual interactions. Throughout the WHO Screening for Sexual Partner Violence Questionnaire, 8.9% (n = 29) of the sample stated to have experienced sexual violence from their current romantic partner. Lastly, the mean score on the RCUSS across the sample reflected reasonably low endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sexual activity. To evaluate the relationships among the presented variables in hypotheses 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 – namely, the relationship between the endorsement of heterosexual scripts (H1), individual (H2 and H3), and IPSV (H4), and the endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sex–bivariate correlations were conducted. The results are provided in Table 1. In the context of individual variables, negative and significant correlations were found between the Internal Consent Scale and the endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sex (r = -.61, p < .001). This indicates higher feelings and perceptions of consent (feeling ready, safe, mentally, and physically aroused, and feeling that the sex was wanted) are associated with less endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sex, thus confirming hypothesis 3b. Similarly, negative significant correlations were found between sexual assertiveness (H2b, r = -.25, p < .001) and the endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sex. Although the strength of the correlation is low, this result confirms our second hypothesis, suggesting that women with lower levels of sexual assertiveness endorse slightly more reasons for consenting to unwanted sex. Positive and significant correlations were found between having experienced IPSV and the endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sex (H4, r = .33, p < .001). This indicates that, although the correlation is not especially strong, individuals who have been subjected to IPSV may be more likely to rationalize or justify their reasons for engaging in sexual activities where consent is ambiguous or absent, suggesting that past victimization can significantly influence one’s perceptions of and behaviors around sexual consent, thus confirming hypothesis 4. Additionally, negative and significant correlations were found between the External Consent Scale and the endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sex (H3a, r = -.36, p < .001). Although the strength of this correlation is low, these results indicate that lower explicit and sexual communication cue behaviors relate to a higher endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sex, thus confirming hypothesis 3a. As expected, negative and significant correlations were found between both sexual satisfaction (H2a, r = -.12, p = .04) and sexual assertiveness (H2b, r= -.25, p < .001), and the endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sex. Although the strength of the correlation is very low, these results confirm our second hypothesis, suggesting that women who endorse more reasons for consenting to unwanted sex report slightly lower levels of sexual satisfaction. In the context of the endorsement of heterosexual scripts, positive and significant correlations were found between the endorsement of traditional sexual scripts (H1a, r = .13, p = .02) and the endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sex. Although the correlation is significant, its strength is weak, thus confirming hypothesis 1a. Differences in Women Who Experienced Unconsented Sex The effect of having experienced sex without consent or not on study variables, a MANOVA was conducted. Results indicated differences between Consenting and Non-consenting women, Wilks’ λ = .85, F (7, 265) = 195.92, p < .001, η2p = .84. First of all, hypothesis 5a was not supported, as sexual consent experiences were not showed a significant effect on the endorsement of traditional sexual scripts, F(1, 271) = 0.76, p = .38, η2p = .003. Regarding individual variables, hypothesis 5b and 5c were also not supported due to the fact that sexual consent experiences did not have a significant effect on sexual satisfaction, F(1, 271) = 1.71, p = .19, η2p = .006, nor sexual assertiveness, F(1, 271) = 2.75, p = .09, η2p = .01. However, according to hypothesis 5d, results indicated a significant effect of sexual consent experiences on both internal consent, F(1, 271) = 1318.32, p < .001, η2p = .83, and external consent, F(1, 271) = 210.14, p < .001, η2p = .44. Specifically, women in the Non-consenting group reported lower levels of internal and external consent strategies than women in the Consenting group (see means in Table 2). Concerning experiences of IPSV, sexual consent experiences significantly shaped experiences of IPSV, F(1, 108) = 16.52, p <.001, η2p = .06, so that women who reported experiencing at least one sexual encounter in which they had felt uncomfortable for not having completely given their consent to participate also reported higher rates of IPSV, thus, confirming hypothesis 5e (see means in Table 2). Finally, results confirmed hypothesis 5f, showing an effect of sexual consent experiences on reasons for consenting to unwanted sex F(1, 271) = 135.01, p < .001, η2p = .33, so that women in the Non-consenting group had higher endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sex than women in the Consenting group (see means in Table 2). Discussion Our findings align with previous literature, highlighting the influence of traditional gender roles and societal norms on sexual interactions. For instance, the positive correlation between traditional sexual scripts and consenting to unwanted sex may reflect a particular societal pattern of gender power dynamics in intimate relationships as discussed by Klein et al. (2018), who found that traditional sexual scripts often involve gendered power inequality, with men displaying dominance and women submission. Nonetheless, our findings indicate that the strength of this correlation, although significant, was weak. This might be attributed to the cultural context of our sample, which consisted of young Spanish university females. These women may have different cultural attitudes towards gender roles compared to other populations, potentially reducing the influence of traditional sexual scripts. As for sexual satisfaction, a consistent trend emerged, indicating that higher levels of satisfaction within the relationship were associated with lower inclinations toward endorsing reasons for consenting to unwanted sex. Nonetheless, the strength of this correlation was very weak. Yet, these findings still align with the idea that relationship dynamics significantly influence sexual behavior and consent. For example, Gadassi et al. (2016) highlighted the mediation role of perceived partner responsiveness between sexual and marital satisfaction, suggesting that the quality of the relationship can influence sexual consent and satisfaction. As expected, similar results were found for sexual assertiveness, consistently indicating that higher levels of sexual assertiveness were related to a lower endorsement of reasons to consent to unwanted sex. This resonates with the findings of Rerick et al. (2022), who showed that increased sexual assertiveness may help individuals reject unwanted sexual advances more effectively, reducing the likelihood of consenting under unwanted circumstances (Rerick et al., 2022). Furthermore, the preference for nonverbal cues is both interesting and concerning. While it indicates an intuitive aspect of human interaction, it also underscores a potential area for misinterpretation and misunderstanding. The relatively lower mean scores for external consent dimensions further suggest that more explicit forms of communication, such as verbal cues, are less utilized. Previous studies have also identified a gap in explicit verbal communication regarding sexual consent. While individuals may regard nonverbal cues as clear indicators of consent, these perceptions can greatly differ among individuals, potentially leading to misinterpretations (Willis & Jozkowski, 2019). Our findings on the high prevalence of non-consensual sexual experiences (44.4%) echoes earlier research, such as Himelein et al.’s (1994) study, which reported a 38.5% incidence of sexual victimization among incoming female college students. These consistent findings across different studies highlight the significant and troubling issue of sexual victimization within the context of higher education. Moreover, the physical and psychological ramifications of non-consensual sex emphasize the need for comprehensive support systems for victims, including medical and psychological assistance (Lincoln et al., 2013). These findings emphasize the urgent need for interventions focused on preventing IPSV and supporting victims in college environments, with studies such as Javidi et al.’s (2023), which demonstrates the effectiveness of targeted educational programs like PACT [Promoting Affirmative Consent among Teens] in improving affirmative consent knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy among adolescents, suggesting similar approaches could be beneficial in higher education settings. Similarly, the significant association between the previous experience of non-consensual sex and higher instances of IPSV found in Study 1 is consistent with literature indicating that IPSV victims often re-experience multiple forms of abuse (Breitenbecher, 2001; Campbell, 2002; Culatta et al., 2020; Edwards & Banyard, 2022; Livingston & Vanzile-Tamsen, 2007; World Health Organization, 2003). In comparing the scores between the Consenting and Non-consenting groups, interesting results emerged. The absence of significant differences between these groups in the endorsement of traditional sexual scripts contrasts with the existing literature, which often highlights the pervasive influence of these constructs on gender roles and sexual behaviors. For instance, studies like Klein et al.’s (2018) and Kiefer and Sanchez’ (2007) suggest that traditional sexual scripts and gendered power dynamics play a significant role in shaping sexual attitudes and behaviors. Yet, our results indicate that these factors may not differentiate between women who consent and those who do not in sexual situations. This could imply that other factors, possibly more nuanced and individualized, are at play in shaping women’s sexual consent decisions and experiences. We invite future researchers to further explore the relationship between these variables with the purpose to gain a better understanding of their relationship. On the topic of sexual satisfaction, our research delved into the complex interplay between sexual satisfaction and experiences of non-consensual sexual encounters. Contrary to expectations based on existing literature, no significant differences were found in sexual satisfaction levels between participants who had experienced non-consensual encounters and those who had not. While previous research often links prior sexual violence to reduced sexual satisfaction (e.g., Katz et al., 2008) and negative future sexual experiences (Leonard et al., 2008), our findings suggest a more nuanced relationship. Factors such as psychological resilience, the nature of the relationship in which the non-consensual experience occurred, and post-incident interpersonal dynamics may influence individuals’ perceptions of sexual satisfaction. Additionally, as suggested by other studies, the psychological aftermath of such experiences can vary greatly, influencing how individuals perceive and report their sexual satisfaction (Dionisi et al., 2012; Katz et al., 2008). Further investigation into these variables is needed to gain a deeper understanding of the phenomena. In the context of sexual assertiveness, our findings indicated no significant differences in sexual assertiveness scores between women with previous non-consensual sex experiences and women without them. This result contrasts with the research by Livingston and Vanzile-Tamsen (2007), which suggests a reciprocal relationship between sexual victimization and assertiveness. It is possible that the characteristics of our sample, such as cultural factors, resilience and support systems, may have influenced these findings, leading to different outcomes than those observed in previous studies. The findings from our study, concerning the significant negative correlations between both the External and Internal Consent Scales and the endorsement of reasons for consenting to unwanted sex, align with and are further substantiated by recent scholarly work. For instance, Walsh et al. (2019) confirm how both internal feelings and external expressions of consent are pivotal in managing sexual consent among undergraduates, highlighting a similar importance of consent dimensions showed in Study 1’s results (Walsh et al., 2019). Previous studies illustrate that internal consent feelings significantly predict external consent communication, demonstrating the interplay between internal emotional states and external behaviors in sexual scenarios (Willis et al., 2021), which supports our findings on the negative relationship between both consent scales and the endorsement of reasons for unwanted sex. This validates the complex dynamics explored in our research, demonstrating how both internal and external aspects of consent are crucial for understanding the reasons and consequences of why women consent to unwanted sex. Our findings also indicated a higher endorsement for consenting to unwanted sex among those with non-consensual sex experiences, resonating with previous literature findings on revictimization and its associated abuses (Breitenbecher, 2001; Livingston & Vanzile-Tamsen, 2007; Messman-Moore & Long, 2000). This suggests a complex interplay between past experiences of unconsented sexual experiences and current attitudes towards sexual consent, emphasizing the critical need for interventions that address both the immediate aftermath of sexual aggression and the long-term psychological impacts that shape survivors’ perceptions of consent and behaviors in future sexual encounters. Finally, given the quantitative findings from this first study, it became apparent that a more nuanced exploration was necessary to fully understand the complexities of dynamics related to sexual consent. Therefore, a second study was designed to qualitatively understand what female students perceive as consent, how they communicate or express it, and the factors they believe are related to consenting to unwanted sex, providing a richer, more contextualized perspective that complements the quantitative data. To gain a more complex and deeper understanding of the research problem, we designed a qualitative study aimed at exploring the nuanced narratives of women regarding sexual consent. This approach was necessitated considering the discrepancies observed in prior literature and the results obtained in Study 1, which may not fully capture the complexity and subjectivity inherent in consent dynamics. Through content analysis of the narratives provided by women, this study seeks to uncover the layers of meaning, context, and personal experience that shape understandings and expressions of sexual consent. By focusing on female sexual experiences and personal accounts, we aim to illuminate the diverse ways in which consent is negotiated, perceived, and articulated. We chose to focus on a university student sample because university settings have been identified as critical environments where cognitive risk factors for sexual aggression victimization and perpetration, such as sexual scripts and acceptance of sexual coercion, are particularly relevant and modifiable (Schuster et al., 2022). Method According to Muylaert et al. (2014), qualitative research examines narratives and behaviors expressed based on each individual’s experience with the world around them. This methodology was chosen for this study to primarily analyze beliefs, perceptions, and feelings from different perspectives, aiming to delve deeply into these aspects. This was necessary to contrast how social discourses influence women’s perceptions of their own experiences regarding sexual consent. Participants The sample for this study involved female university students aged 18 and above (20 years old on average) from Granada. Students in a mandatory course for the criminology degree were invited to be part of a focus group on the topic of sexual consent, offering different time slots. The group with the highest number of participants registered was conducted. The participants did not receive any direct compensation. A focus group consisting of eight participants was conducted to gather rich and diverse insights. Participants were selected based on their willingness to share their perspectives on sexual consent. Design and Procedure: Data Collection The sample collection employed a non-probabilistic convenience sampling approach, targeting readily accessible participants for the researchers. The focus group discussions were recorded using the virtual platform Zoom, facilitated through the University of Granada Network and Communications Service. At the beginning of the group session, the participants were warmly welcomed, and just as the previous study were informed about its purpose, voluntary nature, and the anonymity of their responses. A semi-structured discussion was then conducted, guided by an interview guide, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of sexual consent-related topics. Participants shared their thoughts on diverse aspects of consent, including its conceptualization, communication strategies, gender dynamics, and opinions on recent legislative changes made in Spain. The discussion was moderated to ensure all perspectives were heard, leading to a rich exploration of the subject matter. The session concluded with gratitude expressed to the participants for their valuable contributions. Just as in the previous study, no monetary compensation was provided for participating, but interested participants that attended the focus group would be eligible to participate in the €50 raffle once both studies finished. This study had the approval of the Ethics Committee of the University of Granada for studies involving human participants. Analysis The collected data from the focus group session was transcribed and imported into Atlas.ti 23.0. Subsequently, it was subjected to a content analysis. The analysis was organized using 4 main themes that were established based on the variables and results from Study 1, as well as previous literature on sexual consent. Additionally, we included the topic of the new consent law in Spain, as it was a relevant and current. Based on a predefined procedure, two independent coders categorized the citations of participants opinions and comments regarding the Definitions and Concepts regarding Sexual Consent, Sexual Consent in Different Scenarios, the Influence of Culture and Context, the Psychological Toll of Consent. Ensuring accuracy and reliability of the coding results, first, the researchers independently read the transcribed interview and included the participants citations in the previously established categories. After that, they shared their results and discussed any discrepancies. The agreement index was calculated for the inclusion of citations in every category (k = .80). At the end of the process, total agreement was obtained from the four researchers for the inclusion of the citations. Results Descriptive Analysis After the data analysis process of the four overarching themes (Definitions and Concepts regarding Sexual Consent, Sexual Consent in Different Scenarios, the Influence of Culture and Context, the Psychological Toll of Consent), nine overarching subthemes were established, this way compiling the participants’ experiences, perspectives, beliefs, and perceptions regarding sexual consent (see Table 3). Due to the extensive amount of data collected for this study, the complete content analysis will be included as Supplementary Material. For the purposes of this article, a content analysis was be performed on each identified theme within the collected data. The analysis involved breaking down these themes to understand underlying patterns and categorizations, assessing how different factors interact and influence each other. This process will help to bring light to the complexity and nuances of sexual consent, focusing on various perspectives and interpretations that have emerged from the focus group. Definitions and Concepts regarding Sexual Consent Participants in the focus group explored various aspects of sexual consent, highlighting its complex and multifaceted nature, discussing their understanding of sexual consent, as well as the discrepancies between how they believed sexual consent unfolds in social contexts and Spain’s new sexual consent law. Social Definitions. Participants discussed the different interpretations of sexual consent from individual perspectives within their societal context, emphasizing the role of willingness to engage in sexual activity and the importance of communicating this willingness effectively. Participants noted that sexual consent encompasses not only explicit verbal affirmations but also non-verbal cues and behaviors, indicating that consent can be indicated through active participation in the sexual activity. Woman 1: “Accepting that you want to engage in sexual activity with another person and also ensuring that the other person understands that you accept it.” The discussion also revealed societal perceptions that often prioritize individual sexual pleasure over mutual satisfaction within intimate relationships. This emphasis may overshadow the importance of fostering mutually fulfilling connections, suggesting a cultural shift towards recognizing the need for continuous communication and negotiation of consent. Woman 7: “The people involved have to constantly gauge how the other person is feeling.” Sexual consent was described as a dynamic continuum that requires ongoing awareness and mutual understanding between partners throughout a sexual encounter. For example, Woman 7 said: “… I think it’s something, like, you have to be constantly aware of how the other person is feeling, maybe not necessarily asking outright” … “You can even ask, like: ‘Are you enjoying it or not?’ And both, the people involved, have to constantly gauge how the other person is feeling.” Legal Definitions. Participants discussed Spain’s new sexual consent law, offering insights into how it contrasts with previous legislation and its implications for sexual interactions within the Spanish context. The discussion highlighted a shift in focus from the victim to the perpetrator, which was viewed as a necessary change to align the legal framework with more equitable standards of justice, similar to other types of crimes. Concerns were raised about the lack of multidisciplinary input in the law’s development, suggesting that this could lead to misinterpretations and inefficacies in its application by the judiciary. This emphasizes the need for laws to be crafted with contributions from a diverse range of professionals to better reflect the complex realities of sexual consent. While some participants expressed approval of the new law’s approach to shifting the scrutiny away from victims (Woman 5: “We should never center a crime’s focus on the victim”), others worried about societal tendencies to either oversimplify sexual consent as a mere contractual agreement or overcomplicate it to the extent that it undermines intimacy and mutual understanding in sexual relations, underscoring the delicate balance required in legislating sexual consent, aiming to protect individuals while also maintaining the intimate and personal nature of sexual interactions. As expressed by Woman 7: “It really annoys me that it’s attempted to be simplified so much, like the typical ‘oh, I have to sign a contract,’ and that if you gave consent at the beginning, then everything is permissible”… “it also feels like it’s trying to remove a significant aspect of intimacy, emotional connection, and caring for the other person” ... “there might be a lot of resistance like ‘oh, now I have to conduct an interview while having sex,’ but it’s not that complicated, simply being a bit attentive and asking ‘should I continue? Should I stop? Do you like this?’ It’s not that difficult.” Communication and Sexual Consent. In the discussions on communication and sexual consent, participants emphasized the significant role of non-verbal cues in signaling consent within sexual interactions. These cues include physical proximity, eye contact, and other implicit gestures that suggest a person’s interest or willingness to engage in sexual activities (Woman 1: “They try to touch you, things like that”). However, there was a concern that reliance on non-verbal communication often leads to assumptions of consent, which may not be verbally confirmed. This assumption can make it difficult for individuals to express a change of heart or disinterest as the encounter progresses (Woman 1: “Like it’s taken for granted that both people are accepting to do it.”) Participants also highlighted the importance of sexual assertiveness and explicitly communicating desires and boundaries. It was noted that without clear verbal communication, intentions can be misunderstood, leading to potential discomfort or unwanted advances. This underscores the necessity for both parties in a sexual encounter to engage in open dialogue to ensure that consent is clear and mutual, adjusting as needed throughout their interaction. As expressed by Woman 3: “The actions they (women) carry out can give the other person an understanding of whether you want to do it or not, but in the end, if you don’t express it verbally, it won’t be known exactly. After all, the other person can interpret it one way or another.” This quote captures the essence of the need for explicit communication in determining and maintaining consent. Sexual Consent in Different Scenarios In this category, differences between consent within established relationships and with unfamiliar individuals are evident, as they involve distinct agreements and even fears. This category also encompasses general communication patterns observed during this phenomenon. Interaction within a Couple. In discussions about sexual consent within romantic relationships, participants explored the role of trust and the dynamics that evolve over time between partners. Trust was highlighted as a crucial element that allows individuals to comfortably express their unwillingness to engage in sexual activity without fearing negative repercussions in their relationship. This sense of security enables partners to communicate openly about their feelings and boundaries, which is seen as indicative of a healthy relationship (Woman 4: “They won’t get angry, and it won’t lead to anything negative”). However, some participants noted that the duration of a relationship might complicate the consent process. There was a concern that long-term partners might assume consent based on past interactions, leading to pressure or assumptions that one partner is always willing to engage in sexual activity. Additionally, the issue of consent under the influence of substances like alcohol was discussed, where participants expressed concerns about assumed consent in relationships when one partner is not fully conscious or aware. The significance of these dynamics is encapsulated by Woman 7’s observation: “It’s like she (a friend) took for granted that, being her boyfriend, she consented to anything he could do, even when she was in a bad state, almost unconscious.” Interactions with Unfamiliar Partners. Concerning sexual consent with unfamiliar partners, participants stressed the complexities of communication and the inherent challenges in interpreting non-verbal cues during initial interactions (Woman 4: “You’re trying to gauge their intentions”). The subjectivity of these signals can lead to misunderstandings, with some participants expressing discomfort and fear of refusal, whereas others felt more at ease to communicate dislikes if the person seemed trustworthy. Most encounters with strangers tend to occur within social or party contexts, where the atmosphere and social norms might imply a predisposition to flirt, leading to potential misconceptions about intentions. The influence of alcohol was noted as a significant factor in these settings, as it can diminish one’s ability to give or withhold consent knowingly. Despite these challenges, some participants expressed that interactions with strangers might sometimes allow for clearer boundaries, as they felt less hesitation to express disinterest or stop the encounter altogether compared to interactions with regular partners. This contrasts with traditional views on the dynamics of consent, suggesting that unfamiliar settings might provide a context where consent can be more straightforwardly negotiated. Woman 1 said: “...but maybe if you’ve drunk half a bottle of Larios (Gin), it can take away a bit of the notion of ‘hey, this is how it is’, it depends on how much (alcohol), for each person. There’s a certain limit where you no longer feel capable of saying ‘yes’ or ‘no,’ to give real consent to what you want. It’s like you just go with it.” The Influence of Culture and Context This category discusses how each person’s personal history and social context influence their definition of consent and the consequences this has on the sexual lives of young people. The Sexual Script. Participants shared how societal expectations shape gender roles and behaviors within sexual interactions. Participants noted that societal scripts for sexual behavior often dictate specific roles for men and women, influencing how they perceive and engage in sexual activities (Woman 5: “...I think we have more modesty when it comes to expressing it”). Women described feeling the pressure to adopt more passive roles, reflecting societal norms that expect women to be modest and less initiative in sexual encounters. Conversely, men are often seen as needing to pursue sexual encounters aggressively, a perception that can lead to problematic behaviors including sexual aggression (Woman 4: “In the end, men end up forcing you, forcing women into having sexual relationships...”). Participants pointed out the double standards in how sexual behaviors are judged differently based on gender. Men are often given more freedom and face fewer social consequences for leading an active sexual life, whereas women are judged harshly and labeled negatively for similar behaviors. This difference not only perpetuates sexist attitudes but also restricts open communication about sexual desires and consent, particularly for women who might feel pressured to conform to societal expectations of modesty. For example, Woman 8 captured this gender disparity: “…socially, it’s not as accepted for a woman to take the initiative as it is for a man.” Sexual Education (for both Men and Women). The group discussed the impact of sexual education on perceptions of sexual consent, stressing its importance in both male and female educational programs. It was noted that sexual education is often inadequate and fails to emphasize critical aspects like sexual consent and assertiveness. Participants expressed that, for women, effective sexual education could foster self-awareness and help them recognize situations where consent is given out of fear or pressure (Woman 5: “…action should be taken through sexual education programs so that we, women in general, engage in self-critique”… “and say, ‘I am consenting to this relationship out of fear’”… “‘I don’t deserve this; it’s a crime, and I need to report it’.”). On the other hand, participants shared that, for men, beginning sexual education early in schools could help instill a better understanding of respectful behaviors and potentially reduce instances of sexual aggression. Another significant topic was the role of pornography in shaping sexual expectations, influencing men to form harmful sexual fantasies that do not align with real life consent in sexual interactions. As Woman 1 expressed: “I think porn plays a big role in this, and from a young age, we are not told, ‘Hey, look, this is not real, this can’t be like this in real life, you can’t imitate it because if you do, you’re basically committing a crime because you don’ know if the other person will want it’.” The Psychological Toll of Consent Participants also shared personal perspectives on some overlooked emotional and psychological ramifications that arise from the complexities surrounding sexual consent. Delving into how the lack of a clear, universally accepted understanding of consent affects individuals, particularly women such as themselves, by exploring their lived experiences, emotions, and the social dynamics at play. Emotional Impact and Consequences. The discussions around the emotional impact and consequences of ambiguous sexual consent revealed that uncertainty in establishing clear boundaries can lead to various emotional responses among women, including fear, shame, and ridicule (Woman 5: “Feeling shame also comes from the society we live”). “Shame” is a significant emotion affecting both genders but manifested differently according to the participants. Participants expressed feeling shamed for being sexually active, whereas they believed men might experience shame for lacking sexual activity, highlighting societal double standards that judge sexual behavior. Furthermore, participants expressed that female sexuality is often subjected to mockery, seen as inferior or trivialized in social contexts, which complicates open discussions about sexual desires and experiences (Woman 7: “…sometimes female sexuality, in general, tends to be ridiculed…”). This ridicule can stifle the expression of female sexuality and reinforce gender biases within sexual dynamics. On the other hand, “fear” was by far the most prominent emotion, often stemming from concerns about relationship dynamics or potential violent repercussions from partners. This fear can exacerbate the challenge of setting and enforcing personal boundaries in relationships. As expressed by Woman 7: “Certainly, it is true that, as my colleagues mentioned, I might be a bit afraid that there could be a negative reaction. I haven’t had any reactions that violent, but yes, perhaps there have been reproaches or more subtle things.” Consenting to Unwanted Sex. The conversation among the participants regarding reasons for consenting to unwanted sex shed light on complex motivations and the emotional and social dynamics at play. Some participants expressed that true sexual consent should be accompanied by genuine desire, questioning the validity of consent when desire is absent (Woman 3: “...even if she consents, if she doesn’t really want it, it’s a crime”). Conversely, others noted scenarios where they consented to sex despite low desire, sometimes influenced by the expectation that their feelings might change during the act. Social pressures also play a significant role in decisions about consenting to sex, with societal expectations about sexual activity at certain ages leading to uncomfortable situations. For example, participants expressed that young individuals might feel coerced to engage in sexual activities due to peer pressure or societal norms, even when they are not comfortable or willing. Additionally, the normalization of certain abusive behaviors in social contexts, often influenced by alcohol, drugs, or problematic portrayals in pornography, was discussed as an issue that desensitizes society to the gravity of non-consensual interactions. Woman 7 shared: “But it’s true that, maybe, if I don’t feel like it, and my partner insists, it’s a bit harder for me to say no at first, or maybe I just go along with it. And in the end, I don’t know, I end up enjoying it too.” Discussion Regarding Study 2, we found that women’s narratives on sexual consent were varied and nuanced, often influenced by personal experiences, cultural expectations, and relationship dynamics. Many expressed a need for clearer communication and understanding in consent processes, this way stressing the complexities of implicit versus explicit consent and the role of societal norms and the need for better education regarding this topic. This study’s insights into the societal pressures on men and women described by the participants are in concordance with Hundhammer and Mussweiler’s (2012) findings on how exposure to sexuality cues strengthens gender-based self-perceptions and behavior, aligning with traditional gender stereotypes in sexual contexts. This convergence between the qualitative data from our study and previous research underscores the enduring influence of societal norms and stereotypes on individual behaviors and perceptions regarding sexual consent and gender roles. Participants in Study 2 also emphasized on the complexities of sexual assertiveness, especially the role of non-verbal cues, which, in return, is supported by the work and results of Gil-Llario et al. (2022) and Kim and Choi (2016), who noted a clear relationship between sexual assertiveness, communication, and sexual behavior among college students. Interestingly, participants in Study 2 described high levels of satisfaction within their current relationships. These results raise an intriguing possibility: the likelihood that some participants in this study might have responded to questions about their relationships with a social desirability bias, potentially omitting negative aspects, particularly when aware of being heard by other women as well as the researchers. The social desirability can significantly influence the reporting of intimate partner violence and relationship satisfaction (Visschers et al., 2017). Nonetheless, it is possible that these eight women were simply fortunate enough not to have been victims. The qualitative observations from Study 2 pointed out that sexual consent is often “taken for granted,” especially in the context of an existing positive relationship, potentially obscuring the capacity to revoke consent if the desire changes during the interaction. Contrarily, participants also expressed the importance of verbal communication in asserting what they are willing or not willing to engage in, to circumvent misunderstandings. Similarly, prior research has consistently highlighted the complexity and ambiguity surrounding the communication of sexual consent, often emphasizing the reliance on nonverbal cues over verbal communication (Hickman & Muehlenhard, 1999; Jozkowski & Peterson, 2013). Furthermore, our observation that consent is often “taken for granted” in established relationships aligns with findings from Orchowski et al. (2013), who reported that individuals in ongoing relationships might assume consent based on past sexual history, potentially overlooking the necessity for continuous consent. These findings, alongside existing research, underscore the intricate dynamics of sexual consent within romantic relationships. The contradiction between the implicit assumption of consent in established relationships, and, at the same time, the acknowledged importance of explicit verbal communication, reflects the broader societal challenges in navigating sexual consent, highlighting the discrepancy between idealized sexual consent interactions – where consent is actively negotiated and clearly communicated – and the learned behaviors and expectations shaped by societal norms, which often prioritize implicit understanding and nonverbal cues. Ultimately, these contradictions illuminate the complex interplay between individuals’ desires for clear, explicit consent and the prevailing societal constructs that govern sexual interactions. Study 2’s participants focus on fear as a significant factor in consenting to unwanted sex provides a meaningful understanding of the emotional context of sexual interactions for women. Similarly, recent research shows that fear not only impacts the negotiation of consent but also the compliance with unwanted sexual activities. Quinn-Nilas and Kennett (2018) demonstrated that lower sexual resourcefulness was linked to higher female gender role stress, which was associated with higher endorsement of reasons for consent and subsequently more frequent compliance with unwanted sexual activities. Furthermore, the absence of reported partner violence in Study 2, which was attributed to potential shame and social desirability bias, resonates with the challenges highlighted in IPV disclosure research. Overstreet and Quinn (2013) discussed the significant impact of stigma and fear of judgment on the underreporting of IPV, which aligns with the discrepancy observed between the two studies. The societal pressures and stigma often silence survivors, making it challenging to capture the true prevalence of IPV (Overstreet & Quinn, 2013). The two studies presented in this article aimed to comprehensively investigate the multifaceted aspects surrounding sexual consent among female university undergraduate students. In combination, the results on these studies and the literature collectively indicate that traditional gender roles and sexual scripts may continue to shape sexual consent and behavior, often perpetuating gender inequalities and influencing individual sexual experiences. The discrepancy between the reliance on nonverbal cues and the recognized need for more explicit verbal communication suggests a critical area for educational interventions. There seems to be a clear necessity to enhance sexual communication skills among university students, stressing the importance of verbal consent and ongoing check-ins in sexual encounters to ensure mutual agreement throughout. Such interventions should aim to challenge the norm of assuming consent from nonverbal cues or past relationships, promoting a culture where verbalizing consent and discomfort is not only accepted but expected. Together, these studies accentuate the need for a nuanced understanding of sexual assertiveness, considering both verbal and non-verbal elements, its implications for sexual consent and experiences, and underscore the importance of interventions aimed at enhancing sexual assertiveness, particularly for those with a history of sexual victimization. Moreover, these findings underline the necessity of considering both past experiences and current emotional states in consent dynamics, highlighting the need for better approaches in sexual education and consent negotiations. Furthermore, the disparate findings regarding the experience of intimate partner violence between Study 1 and Study 2 present an intriguing paradox that enriches the discourse on the dynamics of consent and intimate partner violence (IPV) among women. The unanimous absence of reported IPV in Study 2 could initially seem to contradict the findings of Study 1. Nonetheless, despite this absence, participants in Study 2 did acknowledge consenting to sex that they did not desire (e.g., Woman 7: “Certainly, it is true that, as my colleagues mentioned, I might be a bit afraid that there could be a negative reaction. I haven’t had any reactions that violent, but yes, perhaps there have been reproaches or more subtle things”), underlining a complex layer of possible coercive scenarios that do not explicitly manifest as sexual violence but still impact consent dynamics. This discrepancy may also point to the pervasive influence of shame and social desirability bias, which are well-documented barriers to the disclosure of IPV (Overstreet & Quinn, 2013). The fear of stigma, judgment, or further victimization may silence survivors, making it challenging to ascertain the true prevalence of IPV within this cohort. This silence may be further compounded by cultural norms and societal expectations, which may discourage open discussions about such sensitive issues. We encourage new researchers to further expand these inquiries for a better understanding of this phenomena, aiming to explore the nuanced dynamics of consent within intimate relationships, the multifaceted nature of IPV, and specially IPSV, focused on the societal factors influencing the reporting and disclosure of such violence. Limitations The present studies, while providing valuable insights into the dynamics of sexual consent and intimate partner violence among women, are subject to certain limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. Firstly, both studies relied exclusively on female university of Granada student samples, which may limit the generalizability of the results to broader populations. Similarly, Study 2 was conducted with a very small sample of only 8 women, which might not have captured the full spectrum of experiences and perspectives on the issues at hand. These limitations stress the need for future research to consider more diverse and larger samples to enhance the generalizability and depth of understanding of these complex phenomena. Moreover, while we included in our MANOVA sexual orientation and relationship status as control variables, future researchers should further investigate these two variables. Including these variables as independent variables in future analyses could provide additional insights into their roles in sexual consent dynamics. Additionally, it is also recommended for future research to include measures of social desirability, considering that it is a variable that can influence responses from participants regarding similar topics related to sexual consent or aggression. Finally, regarding victimization experiences, it would be interesting for future research to take into account other types of experiences outside of the romantic relationship (such as child abuse; Gobin & Freyd, 2017) or outside the domain of sexuality (such as physical or emotional violence; Juarros-Basterretxea et al., 2022) to verify if these experiences also influence in any way the decision to consent or not. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Gomez-Pulido, E., Garrido-Macías, M., Miss-Ascencio, C., & Expósito, F. (2024). Under the shadows of gender violence: An exploration of sexual consent through spanish university women’s experiences. European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 16(2), 111-123. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2024a10 Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the Colombian Ministry of Education to the first author through the Colfuturo program, and its part of the project titled “Violence against Women: Consequences for Their Psychosocial Well-being” [Violencia contra las mujeres: consecuencias para su bienestar psicosocial]. PID2021-12125OB-I00), funded by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness in 2021. Supplementary Material Supplementary data are available at https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2024a10 References |

Cite this article as: Gomez-Pulido, E., Garrido-Macías, M., Miss-Ascencio, C., & Expósito, F. (2024). Under the Shadows of Gender Violence: An Exploration of Sexual Consent through Spanish University Women’s Experiences. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 16(2), 111 - 123. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2024a10

Correspondence: marta.garrido@uma.es (M. Garrido-Macías); david.martinez@universidadeuropea.es (D. Martínez-Rubio).Copyright © 2025. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS